Amicus CEO John Crowley Outlines Progress in Fabry, Pompe, Batten Therapies

Written by |

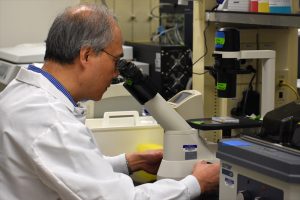

John Crowley, president and CEO of Amicus Therapeutics. (Photos by Larry Luxner)

Pharmaceutical executives rarely make for a sympathetic Hollywood medical drama.

But John Crowley did, and in the nearly 10 years since the release of “Extraordinary Measures” — a tearjerker starring Brendan Fraser as Crowley and Harrison Ford as short-tempered scientist Robert Stonehill — biotech has seen a huge transformation, both on Wall Street and in the lab.

Amicus Therapeutics, which Crowley has led as president and CEO since 2005, now boasts “the largest portfolio of gene-therapy products for rare diseases in development of any company in the world.”

Crowley, 52, made that bold assessment during an hourlong exclusive interview at Amicus headquarters in Cranbury, New Jersey. In 2018, the company reported $91 million in sales from its only drug currently on the market, Galafold (migalastat), for people with Fabry disease.

This year’s revenues are projected to nearly double to between $160 million and $180 million, Crowley said. By 2023, Amicus expects its therapies will treat about 5,000 patients and generate $1 billion in global sales.

Besides the approved medicine Galafold, Amicus now has 14 investigational therapies in its pipeline: two for Fabry, two for Pompe disease, four for Batten disease, and the rest for other rare genetic conditions such as CDKL5 deficiency disorder, Niemann-Pick Type C, Tay-Sachs disease, and mucopolysaccharidoses.

In May 2019, Amicus and the University of Pennsylvania expanded the collaboration they put in place seven months earlier, with Amicus acquiring global exclusive rights to therapies for almost all lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs) as well as 12 prevalent non-LSDs — including Angelman syndrome, Rett syndrome and myotonic dystrophy — coming out of UPenn’s Wilson Lab.

Amicus has agreed to invest $10 million annually into the university’s Gene Therapy Program over the next five years.

“We are now at the earliest stages,” Crowley told Bionews Services, which publishes this website. “If we can get this right in our lifetimes, we can potentially treat and maybe even cure a majority of human genetic diseases. We’re just now unlocking the tools to do that.”

‘Extraordinary Measures’

Visitors to the sprawling Amicus campus are greeted by a huge glass panel engraved with the words: “We believe in the fight to remain at the forefront of therapies for rare and orphan diseases.” Once inside, they pass through hallways lined with museum-like photographs and the life stories of patients with Fabry and Pompe.

Our meeting with Crowley took place only a few weeks after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s May 24 approval of Zolgensma (made by AveXis, a unit of Novartis), the world’s first gene therapy to treat spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). The gene therapy comprises the shell of a genetically engineered virus — the adeno-associated virus (AAV) 9, called a capsid — to deliver a normal copy of the gene that’s mutated in SMA patients.

“That was a milestone moment. I would put it on par with the first human heart transplant,” Crowley said. “Just think, we now have the potential to cure a child of a fatal human genetic disease. That’s been the hope and the dream for a long time in this field. For many years, we thought it was impossible.”

In a way, it’s a reflection of the CEO’s own personal, against-all-odds struggle.

“Extraordinary Measures,” directed by Tom Vaughan and released by CBS Films in 2010, tells the story of Crowley and his wife, Aileen, and their struggle to find a cure for Pompe, which afflicts their daughter, Megan, and son, Patrick. Ford plays Robert Stonehill, a University of Nebraska scientist who believes he’s found a way to treat the crippling disorder — but lacks funding to carry out his research.

“The family dynamics were perfect. On a sound stage, they literally rebuilt our home,” Crowley said of the film. Stonehill was actually a composite character based on a half-dozen scientists who have worked on Pompe over the years.

The entrepreneur said his favorite part of the 106-minute movie — filmed mostly on location in Portland, Oregon — is when his team at the fictional company Priozyme (Novazyme in real life) organizes a lunch for families affected by Pompe disease.

“In Portland, they couldn’t find Pompe kids, so the kids in that scene have either SMA or Duchenne muscular dystrophy,” said Crowley, who has a bit part in the film as a venture capitalist. “They got the science and medicine 100% right. Harrison Ford came to our labs and spent a couple of days there. Since then, he’s become a pretty good friend. We talk regularly.”

He added: “I’ve known a lot of kids with SMA over the years. There’s a young man, Matt Swinton, who lives in Dallas and graduated from the University of Notre Dame in 2012. He’s profoundly affected by SMA. His journey was part of Megan’s inspiration for wanting to go to Notre Dame, and he gave her the belief that if he could do it, she could, too.”

Galafold: A success story

Amicus employs about 600 people in 27 countries, including over 300 at its Cranbury headquarters. The company is in the process of moving all its science and research functions to a 75,000-square-foot Center of Excellence in downtown Philadelphia and is looking at potential sites for gene therapy manufacturing as well.

For now, the company’s only revenue source is the Fabry medication Galafold, which retails for about $315,000 a year.

Fabry disease is caused by a mutation of the GLA gene, which encodes for the alpha-galactosidase A enzyme. Galafold, a so-called “chaperone therapy,” restores the activity of the faulty enzyme in Fabry patients whose GLA mutations are amenable to the medicine.

About 200 U.S. patients are now taking Galafold; worldwide, the number stands at about 800.

“By year’s end, over 1,000 people with Fabry will be using Galafold, which would make it one of the most successful drug launches ever,” Crowley said, adding that Galafold — a capsule given every other day — is “a remarkable opportunity for us to help thousands of people in the future.”

Galafold’s August 2018 approval by the FDA took place under an accelerated program for drugs that fill an unmet medical need. It followed a six-month, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 45 adults with Fabry disease who demonstrated Galafold’s efficacy; likewise, Galafold’s safety was studied in four clinical trials that included 139 Fabry patients.

Galafold’s price tag might seem high, but Crowley said that reflects its benefits.

“Many of those patients are now switching from the approved enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) [Fabrazyme, developed by Sanofi Genzyme], which is $340,000 a year,” he said. “We’re also saving the system thousands of dollars per patient per year. Much of the increased burden of the cost of medicine has to do with price increases after launch. They’ve greatly exceeded even the cost of inflation, but we don’t see a business justification for that.”

Early on, Amicus vowed that the price of the medicine would never rise faster than the U.S. annual consumer price index. So far, he said, Amicus has kept that promise — and that “to date, not a single person in the world has been denied access to Galafold” because of price.

“The insurers appreciate the value of Galafold and knowing they can plan their budgets and knowing what the costs are going to be. It eliminates the risk of uncertainty,” Crowley said. “It’s also good business because we’ve gotten 100% reimbursement from the insurance companies.”

Pompe, Batten drugs follow

Amicus is also developing AT-GAA, an investigational therapy to treat Pompe — the disease that first drew Crowley into the rare-disease space.

The company’s Phase 3 PROPEL trial (NCT03729362) will soon test that therapy in about 100 adult patients with late-onset Pompe disease at sites in 29 countries. Participants will receive either AT-GAA or the current standard-of-care therapy, alglucosidase alfa — marketed as Lumizyme and Myozyme. The trial is still recruiting participants.

That builds on previous data from a Phase 1/2 clinical trial (NCT02675465) which showed that treatment with AT-GAA improved motor and respiratory function in Pompe patients.

“We engineered a cell line and selected an ERT that could be given every other week as an infusion. In addition, we combined it with a small-molecule chaperone to give it additional stability and potency,” Crowley said. “We treated the first patient in April 2016. The results were incredible. We changed the course of the disease for virtually every patient.”

He added: “If they were getting weaker on Lumizyme, we made them stronger. They could walk better and breathe better. All the biomarkers were working in the right direction. All 19 of those patients remain on the Amicus drug to this day.”

Another lucrative opportunity for Amicus is finding a cure for Batten disease, which is seen in two to four of every 100,000 U.S. births.

“The core technology we’re using in Batten came from Dr. Brian Kaspar’s lab [formerly at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio],” he said, referring to programs for the CLN1, CLN3, CLN6, and CLN8 forms of Batten. “We’re using the AAV9 vector [same used in Zolgensma] and delivering it intrathecally (via the spinal canal).”

Amicus is recruiting children for its Phase 1/2 clinical trial (NCT03770572), which will evaluate the safety and effectiveness of its gene therapy for CLN3 Batten disease in children ages 3–10.

Crowley is a vocal proponent of newborn screening programs, because when it comes to neurodegenerative diseases such as Pompe, Fabry and Batten, “it is acutely important to find these kids early” to get the best possible results.

“Hopefully Amicus will have a gene therapy for Batten approved soon. And what a tragedy it would be for a family to find out —only after it’s too late — that there was a cure that could have been given,” he said. “We as a society have a moral obligation to find these children and make sure they have access to these medicines.”