Fabrazyme (agalsidase beta) for Fabry disease

Last updated March 4, 2024, by Marisa Wexler, MS

What is Fabrazyme for Fabry disease?

Fabrazyme (agalsidase beta) is an approved enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) for Fabry disease that’s used to reduce the accumulation of toxic molecules in cells and slow disease progression. It can be used for all patients, 2 and older, regardless of genetic variant, gender, or disease severity.

Fabrazyme is administered by an intravenous infusion, that is, into the bloodstream, and is sold by Sanofi. It was the first ERT specifically approved for treating Fabry disease.

Therapy snapshot

| Brand name: | Fabrazyme |

| Chemical name: | Agalsidase beta |

| Usage: | Enzyme replacement therapy for Fabry disease; used to ease symptoms and slow disease progression |

| Administration: | Intravenous infusion |

How does Fabrazyme work?

Fabry disease is caused by a mutation in the GLA gene, which provides instructions for making alpha-galactosidase A, an enzyme responsible for breaking down the fatty molecule globotriaosylceramide (Gb3 or GL-3).

Because people with Fabry disease cannot make enough functional alpha-galactosidase A, they’re unable to break down Gb3. As a result, the fatty molecule builds up to toxic levels in various tissues and organs, including the kidneys and the heart, causing the damage that leads to disease symptoms.

An enzyme replacement therapy, Fabrazyme contains agalsidase beta, a functional version of the missing alpha-galactosidase A enzyme. This lab-made enzyme, which contains the same sequence as the original enzyme, is made using recombinant DNA technology, meaning it’s produced by cells that have received the GLA gene, which allows it to produce the enzyme.

The replacement enzyme can break down Gb3, helping to prevent the toxic buildup of this fatty molecule.

Who can take Fabrazyme?

Fabrazyme was conditionally approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in April 2003 for people with Fabry disease. The decision, which marked the first U.S. approval specifically for Fabry, was based on reductions in Gb3 accumulation in small blood vessels in the kidney and other cell types, indicating Fabrazyme could ease disease symptoms and improve clinical outcomes.

That approval was converted to a full approval in March 2021 after additional confirmatory trials, making Fabrazyme available in the U.S. for adults and children, ages 2 and older, with confirmed Fabry disease.

Fabrazyme has been approved for Fabry disease in the European Union since 2001. It’s similarly approved in Canada and Japan, where it’s also available as a biosimilar, a biological product that’s almost identical to an approved treatment and generally sold at lower prices.

Who should not take Fabrazyme?

Fabrazyme’s prescribing information does not list any contraindications.

How is Fabrazyme administered?

Fabrazyme is available in single-use vials that contain a white to off-white cake or powder, which must be dissolved in sterile water before being administered. The vials come in two doses, which contain 5 or 35 mg of the agalsidase beta enzyme.

Fabrazyme solutions should be used right after reconstitution and dilution. If immediate use is not possible, the solution can be stored for up to 24 hours at a temperature between 2 C and 8 C (36 F to 46 F).

The therapy’s recommended dose is 1 mg per kg of body weight, given via intravenous infusion every other week. While the initial infusions must be administered at a doctor’s office, hospital, or infusion center, patients may be given the option to receive Fabrazyme at home after several infusions.

Because Fabrazyme can cause severe infusion reactions, medical support should always be readily available when it is administered. Before each infusion, patients also should be treated with antipyretics (fever-reducing medicines) to reduce the risk of those reactions.

In initial infusions, Fabrazyme should be administered at a rate of 0.25 mg/min (15 mg/hour), and this rate cannot be exceeded for patients weighing less than 30 kg (about 66 lbs). For heavier patients, if infusions are well tolerated, the rate can be slowly increased in increments of 0.05 to 0.08 mg per minute, up to a minimum infusion time of 1.5 hours.

Patients who previously showed a positive skin test or tested positive for anti-Fabrazyme IgE antibodies can receive the therapy again after the potential benefits and risks of doing so are weighed individually. This should only be done under the close supervision of a qualified expert.

The first re-administration should involve a low dose (0.5 mg/kg) administered at a slower infusion rate. If the patient tolerates it well, the dose can be increased to the approved 1 mg/kg and the infusion rate can be gradually increased, based on tolerance.

Fabrazyme should not be administered in the same intravenous line with other products.

Fabrazyme in clinical trials

The conditional approval of Fabrazyme was supported in large part by a Phase 3 clinical trial launched in 1999 and its extension study. Continued approval was based on data from a Phase 4 trial, a real-world observational study, and a Phase 2 clinical trial in children and adolescents.

Phase 3 trial

The Phase 3 trial enrolled 58 people with Fabry disease (56 men, two women), ages 16-61, who hadn’t received ERT in the past. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either Fabrazyme or a placebo, every two weeks for 20 weeks (about five months).

The study’s main goal was to compare the number of patients who had no or nearly no Gb3 accumulation in kidney capillaries (small blood vessels) in each group, and to determine Fabrazyme’s safety and efficacy.

Results showed that 69% of patients given Fabrazyme had no or nearly no signs of Gb3 accumulation on kidney biopsies, while none of the patients on a placebo achieved that goal. Similar reductions in Gb3 buildups were observed in the heart (72% of patients of Fabrazyme versus 3% on placebo) and skin (100% vs. 3%).

After completing this part of the trial, all the participants chose to enter an open-label extension study (NCT00074971) and receive Fabrazyme for up to 4.5 years, totaling nearly five years of treatment in those who received Fabrazyme from the start.

After six months in the extension, Gb3 deposits were no longer observed in the kidneys, heart, or skin in most patients, including those who had transitioned to Fabrazyme from a placebo. Comparable long-term clearance of Gb3 was observed at 4.5 years in certain cells of the kidneys and heart. Patients who consistently received Fabrazyme for up to five years maintained normal Gb3 levels in their blood.

Ten-year data, available for 52 patients, showed Gb3 levels remained normal over a decade on Fabrazyme. Most patients (81%) didn’t have any serious health events (e.g., serious kidney problems, heart attack, or stroke) during the extension study, and 94% were alive after 10 years. Moreover, those who initiated treatment at a younger age and had less kidney involvement saw the greatest benefits from the therapy.

Phase 4 trial

The Phase 4 trial (NCT00074984) enrolled 82 adults with advanced Fabry disease (72 men, 10 women), ages 20-72, who had never received enzyme replacement therapy. They were randomly assigned to Fabrazyme or a placebo, administered every two weeks for up to 35 months (nearly three years).

The study’s main goal was to determine if Fabrazyme could extend the time to a clinical significant event, which included a heart attack, kidney failure, stroke, or death, compared with a placebo.

Results showed those events were delayed by 53% with Fabrazyme. Over a median treatment duration of 18.5 months, 27% of patients on the ERT and 42% on a placebo had a clinical event.

The differences in clinical events, however, only reached statistical significance in patients with better kidney function at the start of the trial. Patients with more advanced kidney disease saw similar rates of clinical events with Fabrazyme or a placebo.

Real-world observational study

The observational study was designed to track changes in kidney function, as measured with the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), in people who received Fabrazyme for a long period of time.

The study enrolled 122 people with Fabry, ages 16 and older, who received Fabrazyme, and compared their outcomes with a historical group of untreated patients matched by age, sex, disease type, and starting eGFR scores.

After up to five years of follow-up, patients on Fabrazyme saw a decline in their eGFR scores of 1.5 mL per minute per 1.73 m2 each year, while the annual decline for controls was 3.2 mL per minute per 1.73 m2 each year — a difference of 1.7 points.

Phase 2 trial in children

The pediatric Phase 2 study (NCT00074958) enrolled 16 children and adolescents with Fabry disease, ages 8-16, all of whom were treated with Fabrazyme for about a year. There was no control group.

Data from biopsies showed that, after about six months, Gb3 accumulation in skin capillaries was no longer detectable in any of the 12 patients who’d had detectable levels at the start of the trial. After nearly a year, five patients with available samples continued to have no signs of Gb3 accumulation in the skin.

Gb3 levels in the blood also decreased significantly in the first four weeks of treatment in the male patients, all of whom had higher than normal Gb3 blood levels at the start of the study. These levels remained within normal limits through the study’s end.

Generally, gastrointestinal symptoms such as pain after eating, nausea, and vomiting were significantly eased with treatment, and patient diaries indicated the children had fewer absences from school due to sickness while on Fabrazyme. There also was no decline in kidney function over the one-year study, and no patients reported cardiovascular problems such as stroke.

Common side effects of Fabrazyme

The most common side effects of Fabrazyme reported in clinical studies include:

- upper respiratory tract infection

- chills

- fever

- headache

- cough

- tingling or burning sensations (paresthesia)

- fatigue

- swelling in the limbs (peripheral edema)

- dizziness

- rash.

Allergic reactions

Allergic reactions, including life-threatening reactions called anaphylaxis, have been reported during Fabrazyme infusions. If such a severe reaction occurs, the infusion should be immediately stopped and appropriate supportive care should be given.

Patients who show signs of allergic reaction to Fabrazyme may be successfully rechallenged, that is, the therapy can be started at very low doses given slowly until the patient starts tolerating it without an allergic reaction, before the dose and infusion rate are slowly increased as tolerated. The potential benefits and risks of such a protocol should be weighed on a case by case basis and should only be done under the close supervision of a qualified expert.

Infusion reactions

In clinical trials, more than half of Fabry patients treated with Fabrazyme had adverse reactions during or shortly after receiving the infusion. Some experienced severe infusion reactions, including chills, vomiting, low blood pressure, and paresthesia.

If an infusion reaction occurs, the infusion may be slowed or paused and supportive treatment may be given. If a severe reaction occurs, the infusion should be stopped and appropriate care should be given immediately. Because of the risk of infusion reactions, medical care should always be on standby when an infusion of Fabrazyme is administered.

Patients with compromised cardiac function should be closely monitored for these reactions due to a higher risk of complications.

Use in pregnancy and breastfeeding

Available data from case reports and case series have not identified any major risks associated with using Fabrazyme during pregnancy, and animal studies haven’t identified any detrimental effects of Fabrazyme on fetal development.

There are no data on the presence of Fabrazyme in breast milk and it’s not known if the medication can affect milk production or nursing babies. Patients who are breastfeeding or planning to breastfeed should carefully weigh the benefits of Fabrazyme against the potential risks to the nursing child.

Fabry Disease News is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

Recent Posts

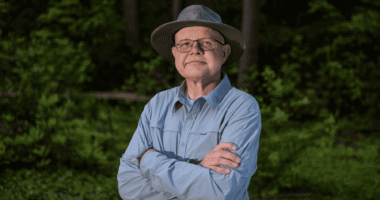

- Jeff’s Journey With Fabry Disease

- Eye vessel abnormalities may signal heart disease in Fabry patients

- We need more oral Fabry disease treatment options that reduce pain

- AMT-191 shows promise, but safety concerns prompt dosing pause

- Guest Voice: Believe us when we say we’re having a bad day

- Sangamo starts FDA submission seeking approval of Fabry gene therapy

- Managing my hypertension has required some trial and error

- Long-term use of lucerastat may protect kidneys in Fabry: Trial data

- Seeking good news as symptom relief eludes my children

- Brain health remains stable for Fabry patients on Galafold: Study