Fabrazyme infusion time may be safely reduced in Fabry: Study

With care, higher infusion rates had no impact on patient safety

Written by |

The duration and rate of Fabrazyme (agalsidase beta) infusion can be safely changed in people with Fabry disease, independently of their body weight, if appropriate care is taken, according to a new study from Japan.

Specifically, an infusion time shorter than 90 minutes or an infusion rate higher than 15 mg/hour — both standard procedure — had no significant impact on treatment safety.

“These findings suggest that infusion times in patients who are tolerating treatment can, with careful monitoring, be gradually decreased,” the researchers wrote.

A shorter infusion time, the team noted, could help reduce the high burden of treatment for people with Fabry.

The study, “Safety and tolerability of agalsidase beta infusions shorter than 90 min in patients with Fabry disease: post-hoc analysis of a Japanese post-marketing study,” was published in the Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. The work was funded by Sanofi, Fabrazyme’s developer.

Different administration of Fabrazyme in US, Japan

Fabry disease is caused by mutations in the GLA gene that result in the production of low levels of the enzyme alpha-galactosidase A (Gal A). GalA is responsible for breaking down certain fatty molecules, and its deficiency leads to the toxic accumulation of those molecules in the body. This, in turn, can lead to damage in several organs, such as the kidneys and heart.

Among the treatments approved to date for the rare genetic disorder is enzyme replacement therapy, known as ERT, which generates the non-functional or missing enzyme. There are two forms of ERT now available in many countries: Replagal (agalsidase alfa) and Fabrazyme (also available as a biosimilar in Japan).

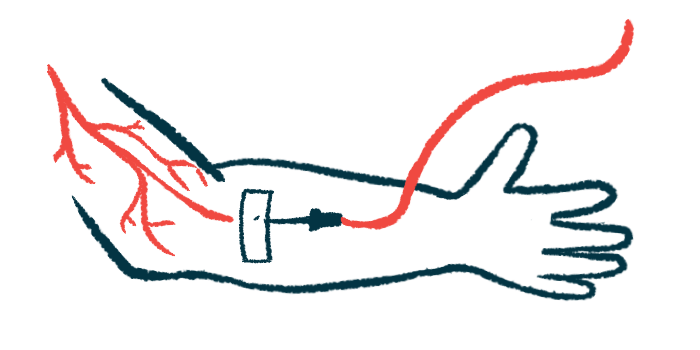

Fabrazyme, approved in the U.S. in 2003, is administered by infusion into the bloodstream (intravenously) every two weeks, at a dose of 1mg/kg of body weight.

In the U.S., infusions lasting at least 90 minutes are recommended for all patients, and both the U.S. and European Union labels mandate infusions not exceeding 15 mg/hr for patients weighing less than 30 kg (around 66 pounds). In contrast, the Japanese label permits infusions of up to 30 mg/hr, potentially allowing for infusions of less than 90 minutes in patients weighing less than 45 kg (around 99 pounds).

However, the safety and tolerability of infusion times that are less than 90 minutes remain to be established.

“While ERT is a mainstay of Fabry disease treatment and confers significant benefits across a variety of disease measures, the need for lifelong, semimonthly infusions carries its own challenges for both patients and caregivers, including disruptions to daily living, impairments to school and work activities, and consequences to family and social life,” the researchers wrote.

“Given the many challenges experienced by patients with Fabry disease and their caregivers as well as the high healthcare costs associated with the disease, any reduction in disease or treatment-related burden could be expected to have a positive impact,” the team added.

No significant differences seen in numbers of adverse events

Now, scientists in Japan analyzed data from 307 people with Fabry disease enrolled in two studies involving patients who were not registered in long-term trials. The goal was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of Fabrazyme in real-world clinical practice.

The first study, called Special Drug Use Investigation of Fabrazyme (NCT 00233870), analyzed the safety and efficacy of the treatment for long-term use. The second, dubbed Drug Use Investigation of agalsidase beta (Registry number: AGAL02904), analyzed the safety profile of the therapy in those not included in the first study.

The majority of patients were men (65.5%), weighing a mean of 54.7 kg (around 120.6 pounds). Six patients had a body weight below 30 kg, and 31 below 45 kg (around 100 pounds). They had started ERT at a mean age of 39.1 years.

Data was available for 2,242 standard infusions, taking at least 90 minutes, and for 436 reduced-duration infusions, taking less than 1.5 hours. Serious adverse events, or SAEs — death and events that were life-threatening, or that resulted in significant disability or hospitalization — were rare (0.6%).

Overall, the frequency of adverse events decreased over the treatment course. They also were less frequent in patients weighing less than 30 kg than in those weighing 30 kg or more, despite having shorter infusion duration. These differences were not significant, however.

Infusion-associated reactions, dubbed IArs, were adverse events occurring during or on the day after the infusion, while overall adverse events were identified as AEs.

IArs were numerically more common when the infusion lasted 90 minutes or longer, compared with durations shorter than 90 min (IARs: 2 vs. 0.9%; AEs: 2.9 vs. 1.4%). The rate of SAEs was similar between the two infusion times (0.4% vs. 0.5%).

According to the researchers, “none of these differences were significant, demonstrating little impact of infusion duration on safety outcomes.”

IAR, AE, and SAE frequencies decreased significantly with increasing infusion rates. In both groups of patients weighing less than 30 kg or 45 kg, the frequency of IARs and AEs decreased with increasing infusion rates, while no differences were observed regarding SAEs for the less-than-45-kg group.

Decreasing infusion time may reduce treatment burden for patients

When considering patients weighing less than 30 kg, both AEs and IARs were significantly less frequent when infusions were delivered at accelerated rates (above 15 mg/h), compared with those given at standard rate (below or equal to 15 mg/h). No SAEs were reported in this group.

“The current 15 mg/hr infusion rate cap mandated by both US and EU labels for [less than] 30 kg patients may not be necessary, and infusion rates can be safely increased when done carefully and gradually in patients with established tolerability,” the researchers wrote.

The data showed that safety events also tended to be less frequent in patients weighing less than 30 kg than in among those weighing 30 kg or more (IARs: 1.8% vs. 2.1%; AEs: 2.3% vs. 3.6%; SAEs: 0.0% vs. 0.6%), although these differences were not statistically significant.

The current 15 mg/hr infusion rate cap mandated by both US and EU labels for [less than] 30 kg patients may not be necessary, and infusion rates can be safely increased when done carefully and gradually in patients with established tolerability.

Moreover, IARs occurred in fewer than 1% of all infusions in patients weighing less than 30 kg — 84% of which were reported in those with an infusion time of less than 90 minutes.

In the overall patient population, a higher proportion of patients with anti-agalsidase beta antibodies experienced more IARs (41.9% vs. 30.7%) and AEs (61.1% vs. 49.3%) than patients without those antibodies. No differences were observed regarding SAEs, or when separately analyzing patients weighing less than 45 kg or 30 kg.

Further, in patients with available data, no changes in antibody status were observed after infusion durations were reduced to less than 90 minutes.

“Given the substantial burden associated with Fabry disease and its treatment, accelerated infusions could be a simple but effective way to confer improvements to patient and caregiver [quality of life],” the researchers wrote.

So doing also may “reduce healthcare resource use, and … improve patient convenience, which may in turn improve adherence to treatment,” the team added.