Fabry disease ERT treatment can be a six-hour commitment

About 1 in 5 patients, half of caregivers said they took time off work

Written by |

People with Fabry disease spend an average of six hours on activities related to a single treatment with an enzyme replacement therapy (ERT), including on travel, waiting, infusions, and other tasks, an observational study suggests.

About 1 in 5 patients and half of caregivers said they took time off work for an ERT infusion, resulting in unpaid hours and out-of-pocket travel expenses.

“The results may help patients and their caregivers better understand the time burden associated with different treatments,” the researchers wrote. The study, “A multi-country time and motion study to describe the experience and burden associated with the treatment of Fabry disease with enzyme replacement therapy with agalsidase alfa and agalsidase beta,” was published in the Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. Amicus Therapeutics, which sponsored the study, markets Galafold (migalastat), an approved oral therapy for Fabry disease.

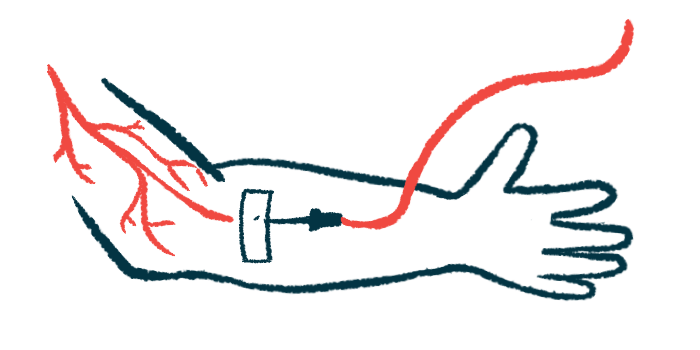

Fabry disease is a rare inherited disorder caused by the deficiency or dysfunction of the alpha-galactosidase enzyme (alpha-Gal A), which causes certain fat molecules, namely globotriaosylceramide (Gb3), to accumulate to toxic levels within multiple cell types.

ERTs are the standard treatment for Fabry and contain a lab-made version of alpha-Gal A intended to clear Gb3 from cells, thereby slowing or preventing the progression of organ damage.

Fabrazyme (agalsidase beta) and agalsidase alfa, which is sold outside the U.S. as Replagal, are ERTs and both are administered via infusion into the bloodstream every two weeks, resulting in lifelong treatment. Frequent visits to a hospital or clinic are required and infusion times can range from 40 minutes for agalsidase alfa to five hours for Fabrazyme. This will likely place a considerable burden on patients, their caregivers, and healthcare services. Treatment in a hospital typically occurs at specialized Fabry centers, which may be far from a patient’s residence.

Cost of treatment — in time spent

“Real-world data on the time, cost, and burden associated with the administration of ERTs are limited,” wrote a team led by scientists at Amicus, who conducted an observational study (NCT04281537) to measure the burden of ERT infusions on 76 patients with Fabry disease (33% women) and six caregivers recruited from Brazil, Taiwan, Japan, and Turkey. Most (63%) received Fabrazyme, while 37% were given agalsidase alfa.

Healthcare providers spent about 2.5 hours on an ERT session, including pre-infusion, infusion, and post-infusion tasks. The total mean time was almost two hours for agalsidase alfa and nearly three hours for Fabrazyme. More than six hours were spent on all the activities related to an ERT infusion, including travel, waiting, the infusion process, and other tasks.

“These results highlight the considerable burden on patients that may have wider-reaching impacts on other aspects of the patient’s life and their health and well-being,” the researchers wrote.

A fifth of patients reported taking time off work for treatment, ranging from 11% in Turkey to 50% in Japan. Patients also reported spending a mean 6.6 paid hours and 5.3 unpaid hours absent from work. Half of the caregivers took time off work for treatment.

Total out-of-pocket travel expenses for patients were $58 in Japan, $33.9 in Brazil, $21.9 in Taiwan, and $16.5 in Turkey, showing that “some patients are incurring expenses that may exceed hundreds or even over a thousand U.S. dollars over the course of a year to travel to their hospital every [two] weeks for their treatment,” the researchers wrote.

The participants also completed the Work Productivity and Activity Index questionnaire, which measures absenteeism, impaired work productivity, and limitations in activity due to health problems over the past seven days.

Of the 76 patients, 39% were employed full time, 7% part time, and 3% employed, but on long-term sick leave. On average, patients missed more work time due to health issues in the one to seven days after an ERT infusion than in a non-infusion week (5.0% vs. 3.7%).

Work productivity was also affected, with more presenteeism reported after an infusion than during a non-infusion week (28.6% vs. 22.6%). The overall work impairment due to health was higher after an infusion (28.9% vs. 25.7%). Daily life activities were compromised during infusion and non-infusion weeks (30.8% vs. 32.3%).

“The findings of this study help fill an important evidence gap and provide a more complete picture of the burden associated with standard-of-care ERT for [Fabry],” the researchers wrote. “An oral treatment option for patients with [Fabry] who are eligible may be an appropriate alternative.”